The Infinite Worlds

[The work of Copernicus, Galileo and Descartes produced] the revolution from the medieval to the modern universe. It still remained for men to effect an emotional readjustment, to realize the full significance of this change in the place of man in the world. Two great thinkers, the one inspired by Copernicus, the other by Descartes, stand out as the earliest representatives of this readjustment. Giordano Bruno in the sixteenth century really felt the infinity of the universe, Benedict Spinoza, in the seventeenth really assimilated the reign of mechanical law. Each made a religion of the new science.

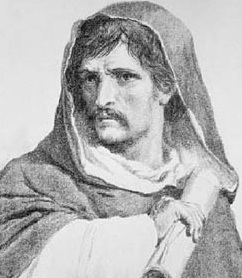

Bruno, a Dominican friar who fled the cloister and wandered up and down Europe lecturing and disputing in the universities of Rome, France, England, Germany, Geneva, to fall at last a victim to the Inquisition and die in flames in Rome, the great martyr of the new science, was a man whose soul was set on fire by the Copernican discoveries.

To him the great achievement of the new astronomy was its principle of the relativity of all place and motion. If the sun is the center and not the earth as Copernicus taught, where then is the real center of the universe? In his boyhood his native mountain of Cicada seemed the center of the world, and far-off Vesuvius on the outer rim. When he climbed climbed Vesuvius, Cicada faded into insignificance. Which was the center? Can there be any real center? If not the earth, why the sun? A candle flame grows smaller as we recede; why may not suns do likewise? Why, indeed, may not all the stars be themselves suns and each new sun appear to itself the center of the universe?

Where, then, are its limits? Has it limits? Is it not rather infinite, an infinity of worlds like our solar system? There must be hundreds of thousands of suns, and about them planets rolling, each one, perhaps, inhabited, by beings possibly better, possibly worse, than ourselves. Throughout, nature must be the same, everywhere worlds, everywhere the center, everywhere and nowhere. The narrow bonds of the Ptolemaic world, which even Copernicus had not really broken fly asunder for Bruno as he launches his soul into infinite space.

But what, then, are the consequences for man? In such a world, what becomes of the central episode of Christianity? No longer is man the only Child of God; perhaps he is lost in the infinity of worlds. “Man is no more than an ant in the presence of the infinite. And a star is no more than a man.” How can man be the central figure in such a world?…

From

such a nightmare the soul of Bruno shrank. No, God cannot be found

anywhere in the boundless universe just because He must be everywhere…

The power that animates the whole must be that which lives in each

of the parts. And so Bruno passed from Platonism to a mystic pantheism,

feeing the pulse of God in every natural force, seeing and adoring

his glory in the vast profusion of that universe that can be but

his body. Losing God from the world, he found Him again is the rhythmic

life of the universe, in the falling waters and the ripening grain

and in the circling of sun on sun.

Up and down Europe Bruno wandered, on fire with his vision, the

"Excubitor," he called himself, the awakener of sleeping

minds.

[Giordano Bruno 1548–1600 burned at the stake for these beliefs]

“I hold the universe to be infinite as a result of the infinite divine power: for I think it unworthy of divine goodness and power to have produced merely one finite world when it was able to bring into being an infinity of worlds.

Wherefore I have expounded that there is an endless number of individual worlds like our earth. I regard it with Pythagoras as a star, and the moon, the planets and the stars are similar to it, the latter being of endless number.

All these bodies make an infinity of worlds; they constitute the infinite whole in infinite space - an infinite universe, that is, containing innumerable worlds. So that there is an infinite measure in the universe and an infinite multitude of worlds.”