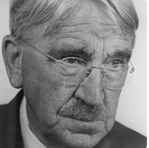

Reading on: Reactions to the new naturalism

Dewey, John in Living Philosophies, Simon and Schuster, New York 1931 [abridged–700 words] — what we experience is the real world – and it is forever changingIf we once start thinking no one can guarantee where we shall come out, except that many objects, ends and institutions are doomed. Every thinker puts some portion of an apparently stable world in peril and no one can wholly predict what will emerge in its place.

It is a commonplace that since the seventeenth century science has revolutionized our beliefs about outer nature, and it is also beginning to revolutionize those about man.

When our minds dwell on this extraordinary change, they are likely to think of the transformation that has taken place in the subject matter of astronomy, physics, chemistry, biology, psychology, anthropology, and so on. But great as is this change, it shrinks in comparison with the change that has occurred in method. The latter is the author of the revolution in the content of beliefs. The new methods have, moreover, brought with them a radical change in our intellectual attitude and its attendant morale. The method we term “scientific” forms for the modern man the sole dependable means of disclosing the realities of existence. It is the sole authentic mode of revelation. This possession of a new method, to the use of which no limits can be put, signifies a new idea of the nature and possibilities of experience. It imports a new morale of confidence, control, and security…

In science and in industry the fact of constant change is generally accepted. Moral, religious, and articulate philosophic creeds are based upon the idea of fixity. In the history of the race, change has been feared. It has been looked upon as the source of decay and degeneration. It has been opposed as the cause of disorder, chaos, and anarchy. One chief reason for the appeal to something beyond experience was the fact that experience is always in such flux that men had to seek stability and peace outside of it. Until the seventeenth century, the natural sciences shared in the belief in the superiority of the immutable to the moving, and took for their ideal the discovery of the permanent and changeless…

In this attachment to the fixed and immutable, both science and philosophy reflected the universal and pervasive conviction [that]… impermanence meant insecurity; the permanent was the sole ground of assurance and support amid the vicissitudes of existence… The good life was one lived in fixed adherence to fixed principles.

In contrast with all such beliefs, the outstanding fact in all branches of natural science is that to exist is to be in process, in change. Nevertheless, although the idea of movement and change has made itself at home in the physical sciences, it has had comparatively little influence on the popular mind as the latter looks at religion, morals, economics, and politics. In these fields it is still supposed that our choice is between confusion, anarchy, and something fixed and immutable.

…Ideals of fixity persist in a moving world. A philosophy of experience will accept at its full value the fact that social and moral existences are, like physical existences, in a state of continuous if obscure change. It will not try to cover up the fact of inevitable modification, and will make no attempt to set fixed limits to the extent of changes that are to occur. For the futile effort to achieve security and anchorage in something fixed, it will substitute the effort to determine the character of changes that are going on and to give them in the affairs that concern us most some measure of intelligent direction…

Wherever the thought of fixity rules, that of all-inclusive unity rules also… Consider the place occupied in popular thought by search for the meaning of life and the purpose of the universe. Men who look for a single purport and a single end either frame an idea of them according to their private desires and tradition, or else, not finding any such single unity, give up in despair and conclude that there is no genuine meaning and value in any of life’s episodes.

The alternatives are not exhaustive, however. There is no need of deciding between no meaning at all and one single, all-embracing meaning. There are many meanings and many purposes in the situations with which we are confronted— one, so to say, for each situation. Each offers its own challenge to thought and endeavor, and presents its own potential value.

It is impossible, I think, even to begin to imagine the changes that would come into life—personal and collective— if the idea of a plurality of interconnected meanings and purposes replaced that of the meaning and purpose. Search for a single, inclusive good is doomed to failure. Such happiness as life is capable of comes from the full participation of all our powers in the endeavor to wrest from each changing situation of experience its own full and unique meaning. Faith in the varied possibilities of diversified experience is attended with the joy of constant discovery and of constant growing. Such a joy is possible even in the midst of trouble and defeat...