Readings on: Relating to the universe

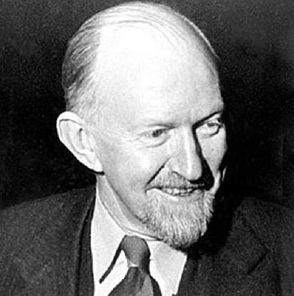

Simpson, George Gaylord This View of Life, Harcourt, Brace & World New York 1964 “The World into Which Darwin Led Us” abridged [2500 words] — a changed conception of human beings

It has often been said that Darwin changed the world… Most, although not quite all, of our technology would be the same if Darwin’s work had not been done, by him or anyone else. Doubtless we would in that case still have our same traffic jams; horror movies, bubble gum, and other evidences of high civilization. The paraphernalia of civilization are, however, superficial. The influence of Darwin, or more broadly of the concept of evolution, has had effects more truly profound. It has literally led us into a different world.

How can that be? If evolution is true, it was as true before Darwin as it is today. The physical universe has not changed. But our human universes, the ones in which we really have our beings, depend at least as much on our inner perceptions as on the external, physical facts…

The world in which modern, civilized men live has changed profoundly with increasingly rational, which is to say eventually scientific, consideration of the universe. The essential changes came first of all from the physical sciences and their forerunners. In space, the small saucer of the savage became a large disk, a globe, a planet in a solar system, which became one of many in our galaxy, which in turn became only one nebula in a cosmos containing uncounted billions of them. The astronomers have finally located us on an insignificant mote in an incomprehensible vastness—surely a world awesomely different from that in which our ancestors lived not many generations ago.

As astronomy made the universe immense, physics itself and related physical sciences made it lawful. Physical effects have physical causes, and the relationship is such that when causes are adequately known effects can be reliably predicted. We no longer live in a capricious world. We may expect the universe to deal consistently, even if not fairly, with us. If the unusual happens, we need no longer blame kanaima (or a whimsical god or devil) but may look confidently for an unusual or hitherto unknown physical cause. That is, perhaps, an act of faith, but it is not superstition. Unlike recourse to the supernatural, it is validated by thousands of successful searches for verifiable causes. This view depersonalizes the universe and makes it more austere, but it also makes it dependable.

To those discoveries and principles, which so greatly modified concepts of the cosmos, geology added two more of fundamental, world-changing importance: vast extension of the universe in time, and the idea of constantly lawful progression in time…

With dawning realization that the earth is really extremely old, in human terms of age, came the knowledge that it has changed progressively and radically but usually gradually and always in an orderly, a natural, way. The fact of change had not earlier been denied in Western science or theology—after all, the Noachian Deluge was considered a radical change. But the Deluge was believed to have had supernatural causes or concomitants that were not operative throughout the earth’s history. The doctrine of geological uniformitarianism, finally established early in the nineteenth century, widened the recognized reign of natural law. The earth has changed throughout its history under the action of material forces, only, and of the same forces as those now visible to us and still acting on it.

The steps that I have so briefly traced reduced the sway of superstition in the conceptual world of human lives. The change was slow, it was unsteady, and it was not accepted by everyone. Even now there are nominally civilized people whose world was created in 4004 BC. Nevertheless, by early Victorian times the physical world of a literate consensus was geologically ancient and materially lawful in its history and its current operations. Not so, however, the world of life; here the higher (or at least later) superstition was still almost unshaken. Pendulums might swing with mathematical regularity and mountains might rise and fall through millennia, but living things belonged outside the realm of material principles and secular history. If life obeyed any laws, they were supernal and not bound to the physics of inert substance. Beyond its original, divine creation, life’s history was trivial. Its kinds were each as created in the beginning, changeless except for minor and obvious variations.

Perhaps the most crucial element in man’s world is his conception of himself. It is here that the higher superstition offered little real advance over the lower. According to the higher superstition, man is something quite distinct from nature. He stands apart from all other creatures; his kinship is supernatural, not natural… Another subtler and even more deeply warping concept of the higher superstition was that the world was created for man. Other organisms had no separate purpose in the scheme of creation…

The fact—not theory—that evolution has occurred and the Darwinian theory as to how it has occurred have become so confused in popular opinion that the distinction must be stressed. The distinction is also particularly important for the present subject, because the effects on the world in which we live have been distinct. The greatest impact no doubt has come from the fact of evolution. It must color the whole of our attitude toward life and toward ourselves, and hence our whole perceptual world. That is, however, a single step, essentially taken a hundred years ago and now a matter of simple rational acceptance or superstitious rejection…

The import of the fact of evolution depends on how far evolution extends, and here there are two crucial points: does it extend from the inorganic into the organic, and does it extend from the lower animals to man? In The Origin of Species Darwin implies that life did not arise naturally from nonliving matter, for in the very last sentence he wrote, “. . . life . . . having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one. . .” (The words by the Creator were inserted in the second edition and are one of many gradual concessions made to critics of that book.) Later, however, Darwin conjectured (he did not consider this scientific) that life will be found to be a “consequence of some general law”— that is, to be a result of natural processes rather than divine intervention. He referred to this at least three times in letters unpublished until after his death, the one from which I have quoted being the last letter he ever wrote (28 March 1882 to G. C. Wallich; Darwin died three weeks later)…

… it was evident to evolutionists from the start that man cannot be an exception [to organic development through evolution]. In The Origin of Species Darwin deliberately avoided the issue, saying only in closing, “Light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history.”…

Twelve years later (in 1871) Darwin published The Descent of Man, which makes it clear that he was indeed of the opinion that man did originate by evolution. No evolutionist has since seriously questioned that [idea]...

Evolution is, then, a completely general principle of life. (I refer here, and throughout, to organic evolution. Inorganic evolution, as of the stars or the elements, is quite different in process and principle, a part of the same grand history of the universe but not an extension of evolution as here understood.) Evolution is a fully natural process, inherent in the physical properties of the universe, by which life arose in the first place and by which all living things, past or present, have since developed, divergently and progressively.

This world into which Darwin led us is certainly very different from the world of the higher superstition. In the world of Darwin man has no special status other than his definition as a distinct species of animal. He is in the fullest sense a part of nature and not apart from it. He is akin, not figuratively but literally, to every living thing, be it an ameba, a tapeworm, a flea, a seaweed, an oak tree, or a monkey—even though the degrees of relationship are different and we may feel less empathy for forty-second cousins like the tapeworms than for, comparatively speaking, brothers like the monkeys. This is togetherness and brotherhood with a vengeance, beyond the wildest dreams of copy writers or of theologians.

Moreover, since man is one of many millions of species all produced by the same grand process, it is in the highest degree improbable that anything in the world exists specifically for his benefit or ill. It is no more true that fruits, for instance, evolved for the delectation of men than that men evolved for the delectation of tigers. Every species, including our own, evolved for its own sake, so to speak. Different species are intricately interdependent, and also some are more successful than others, but there is no divine favoritism. The rational world is not teleological in the old sense. It certainly has purpose, but the purposes are not imposed from without or anticipatory of the future. They are internal to each species separately, relevant only to its functions and usually only to its present condition…

Evolution is an extremely complex process, and we are here interested mainly in the effects of the concept on our world rather than in the process for its own sake…

The theory [of evolution]… obviously does not yet answer all questions or plumb all mysteries… It casts no light on the ultimate mystery— the origin of the universe and the source of the laws or physical properties of matter, energy, space, and time. Nevertheless, once those properties are given, the theory demonstrates that the whole evolution of life could well have ensued, and probably did ensue, automatically, as a natural consequence of the immanent laws and successive configurations of the material cosmos. There is no need, at least, to postulate any non-natural or metaphysical intervention in the course of evolution.

That conclusion has been questioned or opposed not only by many philosophers and theologians but also by a comparatively small number of scientists. The alternatives occasionally supported by scientists or scientific philosophers, and therefore pertinent here, comprise many shadings and variations of opinion, but most of them can be placed in the rubrics of vitalism and finalism.

The vitalists maintain that life is an essence or principle in itself, absent in nonliving matter and not reducible to the interaction of fully material factors. They usually point to a directedness or apparent purposefulness in the development and activities of living things and conclude that the vital, nonmaterial essence within them is a controlling influence in evolution. The finalists maintain that the evolutionary history of life has a preordained over-all pattern which, at least until the appearance of man, was purposefully directed toward a future goal or end. There is no absolute logical necessity that vitalism and finalism should go together, but the ideas are related if only because both are to some degree non-naturalistic and, in that sense, nonmaterialistic. More often than not, vitalists are finalists and finalists are vitalists...

Most scientific evolutionists since Darwin have followed his lead in this matter and have continued to seek material, natural explanations of evolution without necessarily taking any overt stand on vitalism or finalism. To the extent that vitalism and finalism are nontestable, that attitude is justified, and the scientist, as scientist, has no right to go further than to repeat the classic remark that he has no need of that hypothesis. However, I do not see how the matter can in all candor be dropped at that point even by the least philosophical of evolutionists, for there are repeated claims by vitalists and finalists that their views are testable and that there is need for that hypothesis…

The sort of testable evidence that would suggest vitalism or finalism would be the steady progression of life, and of each of its evolving lineages, toward a final and transcendentally worthy goal. That is not, in fact, what the known record of life’s history shows. There is no clear over-all progression. Organisms diversify into literally millions of species, then the vast majority of those species perish and other millions take their places for an eon until they, too, are replaced. If that is a foreordained plan, it is an oddly ineffective one. Single lineages, when they can be followed for long, often do show rather steady change, but not indefinitely. They become extinct, or, if they survive, the directions and rates of their evolution change. They evolve exactly as if they were adapting as best they could to a changing world, and not at all as if they were moving toward a set goal. As for the directedness that does indeed characterize vital processes, it is amply explicable by natural selection without requiring any less mundane cause.

That sort of evidence, with much else in detail, convinces me, at least, that the hypotheses of vitalism and finalism are not necessary. Everything proceeds as if they were nonexistent. That does not prove that they are untrue, but it makes their positive adoption unjustified…

Let me summarize and conclude as to this world into which Darwin led us. In it man and all other living things have evolved, ultimately from the nonliving, in accordance with entirely natural, material processes. In part that evolution has been random in the sense of lacking adaptive orientation... The mechanism of orientation, the nonrandom element in this extraordinarily complex history, has been natural selection, which is now understood as differential reproduction.

Man is one of the millions of results of this material process. He is another species of animal, but not just another animal. He is unique in peculiar and extraordinarily significant ways. He is probably the most self-conscious of organisms, and quite surely the only one that is aware of his own origins, of his own biological nature. He has developed symbolization to a unique degree and is the only organism with true language. This makes him also the only animal who can store knowledge beyond individual capacity and pass it on beyond individual memory. He is by far the most adaptable of all organisms because he has developed culture as a biological adaptation. Now his culture evolves not distinct from and not in replacement of but in addition to biological evolution, which also continues...

[This is] a world in which man must rely on himself, in which he is not the darling of the gods but only another, albeit extraordinary, aspect of nature. [This idea] is by no means congenial to the immature or the wishful thinkers. That is plainly a major reason why even now, a hundred years after The Origin of Species, most people have not really entered the world into which Darwin led—alas—only a minority of us. Life may conceivably be happier for some people in the older worlds of superstition. It is possible that some children are made happy by a belief in Santa Claus, but adults should prefer to live in a world of reality and reason.